I came across this post on LinkedIn yesterday and I wanted to elaborate bit more on why you should not include the ones that predict only treatment, for the purpose of making it more intuitive. It’s hidden in regression…

In many textbooks, the way to estimate linear regression parameters (without calculus/iterative solutions) is only given in a bivariate setting. When moved to “multivariate”, they let the programming do the job. And I get it, it makes sense, since this is what we’re doing in real life when we’re at the job. However, a simple expression can make things way smoother:

\(\displaystyle y_i = \beta_0 + \beta_1{X_1} + \beta_2{X_2} + ... + \beta_p{X_p}\)

We can get any beta by:

\(\displaystyle \frac{\text{Cov}(Y_i, r_p)}{\text{Var}(r_p)}\) where \(r_p\) is residuals from a regression: \(X_p\) ~ \(X_{-p}\)

In plain English, \(r_p\) is the residuals from a regression of \(X_p\) onto other predictors that are not \(X_p\). That’s why the interpretation in regression is as value of variable \(X_p\), after accounting for all the other predictors. Since \(r_p\) is the portion of the \(X_p\) that is purged from other variables (i.e., part of \(X_p\) that cannot be explained by other predictors).

Now, let’s think about this throughly (and about how beatiful this is) and I actually mentioned this on the last interpretablog post (actually, stuff above can be understood from that post as well): If there’s high multicollinearity, there wouldn’t be much variance left since most of the variable would get explained by others. Well, if that variable is the treatment, that would cause issue right? Since there isn’t much variance left in the treatment.

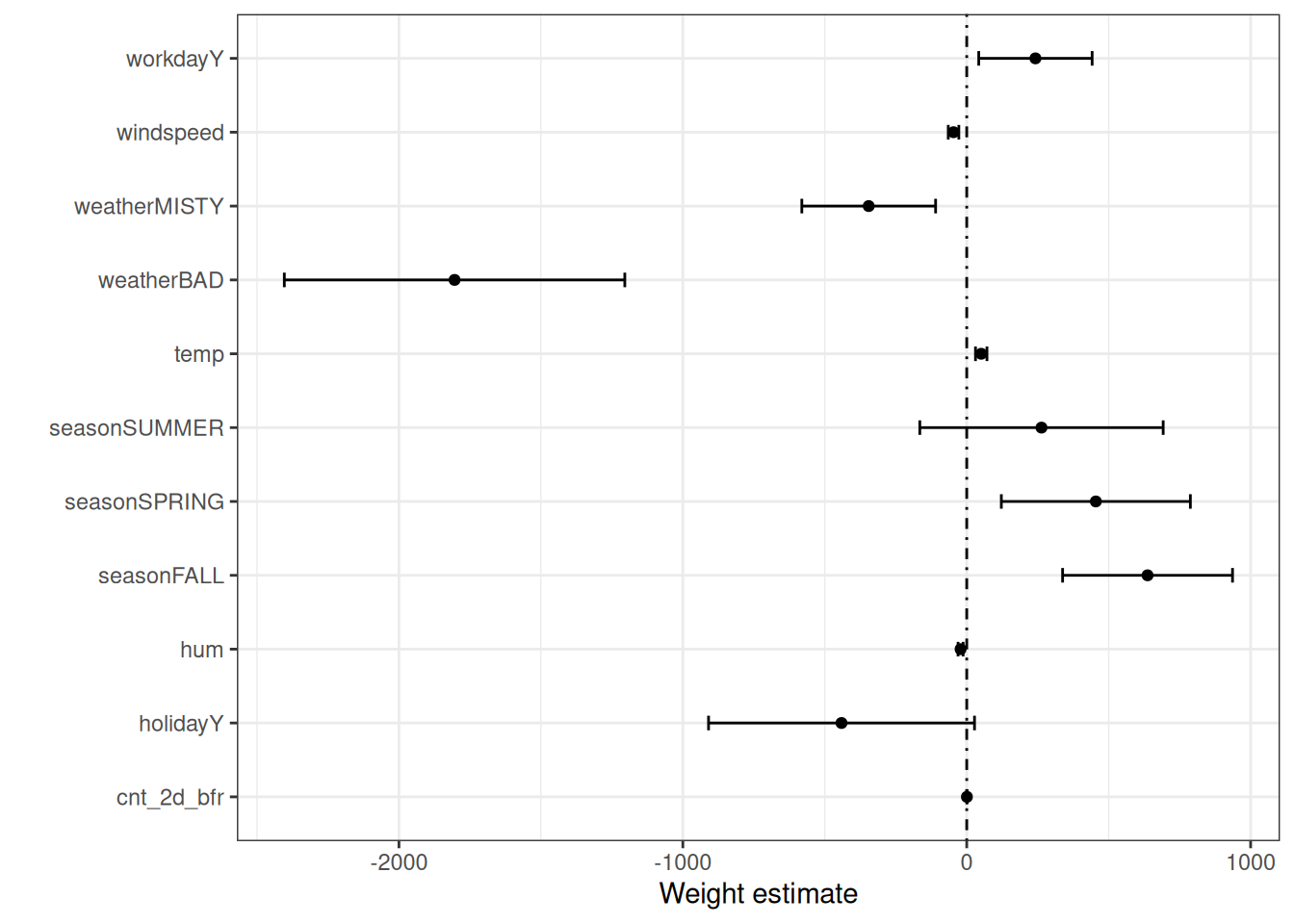

Let’s put it this way: Imagine you want to estimate the effect of a campaign. If every customer has taken the campaign, hence no variance, you’d have hard time estimating its effect, right? Ofc., this is not specific to the “treatment”. You may have actually came across this before, if you have ever looked at a weight plot. When there isn’t much variance in a variable, the weight plot would show its “lines” wider — reflecting its large standard error, in line with how difficult it is to estimate its coefficient. If you haven’t seen one before, here’s one below that I borrowed from Molnar’s Interpretable ML.

Well, about “including the good predictors of the outcome”: Even if they are not confounders, you should include good predictors of the outcome to reduce its variance. This is not a must but it should help specifically in situations where most of the variance can be explained by other factors that are not the treatment. Hence, you’re trying to understand how much of the leftover variability does your treatment explains, after accounting for the other factors that have BIG say in the outcome.

I usually think of “gene” related examples: Like estimating the effect of diet on adolescent height. I suspect gene to explain big portion of height, so controlling for gene would help. I am not sure if this is proper in scientific sense, but you got the idea.

I hope you enjoyed reading this. I believe there are a lot of issues in internalizing the regression so I’ll follow this one up with unidentifiability issue, related to including variables.

See you next time.